One day I complained to my aunt about some little thing that I cannot recollect now. My aunt said to me, "Your mother made you."

I did not like to be told that I resembled my mother. "What do you mean?"

"You don't remember how much you loved your mom."

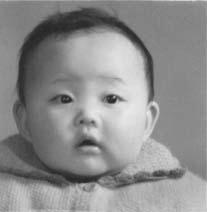

Mom had told about me when I was a six-month-old baby:

"Oh, you loved Mommy. Every afternoon at five o'clock sharp, you had to be in my arms, or just near me. You'd cry like being murdered with anyone else, even with your Dad. I just put my arms around you, and you'd be quiet and happy like an angel. Everyday at five o'clock, Nanny had to rush you into my work place. It was like a spell."

"Some days I was so busy that I couldn't hold you. Nanny cooed you with her crude lullabies, while you kept on bawling like a little devil. One day you distracted me so much that I made a deposit and forgot to take the man's cash. He walked away with a hundred yuan, my three months' salary."

"You must've known she got off work at five o'clock," my aunt said. "But bank tellers had to stay a little late to cash checks."

"Your mother was very capable and responsible, so nice too that everyone at work loved her. She was young and ambitious, and hated the notion that she couldn't perform as well as anyone after she had a child. You and your five o'clock alarm weren't something she looked forward to every day."

"One day you cried so hard that she messed up an account. She got mad: why did you have to keep on bawling? Couldn't you see she was working? She slapped you and you cried harder. Then she scooped you up in her arms and you stopped crying. Just like that. You loved her like crazy. She was your mom, and you were just a normal kid."

"I was normal?" I asked with a smile.

"Yes," my aunt said. "You would've grown up a happy girl if she had kept you. When you were nine months old, your mother was pregnant again with your brother. Your father was working in another town. She became overwhelmed having to take care of you and work a full-time job, so she sent you to us."

"You were left with your grandparents, uncles and aunts. You were so chubby and cute that we all rushed to hold you. The day went by fast, then at five o'clock you started crying. You cried and screamed as if you didn't want to live. Your grandma asked me if I left a needle on your clothes and I looked everywhere but couldn't find one. We hustled and bustled, tried everything, but you kept on bawling until you turned hoarse and gagged, and the house felt like shaking. Ah, it was a nightmare; a nightmare every night until a week later, you got a fever."

"But I don't remember I cried that much," I said.

"You weren't a crybaby. After you got well, you rarely cried; you didn't laugh, either. It was odd to see a child who didn't laugh or cry."

"You seemed to have grown up all of a sudden, but you were timid and weak. You couldn't walk when you were eighteen months old. One day I opened my arms and asked you to walk over. You panted and said, 'Babe's scared,' and wouldn't move a step. I've never heard a kid talk before she could walk, that was the cutest thing."

"Maybe you didn't have enough your mother's milk and it weakened your immune system. You were sick all the time, and hospitalized when you were not even two years old. When your uncle went to check you out, you had packed all your stuff and waited for him at the door. You separated dry and wet things, and stuffed a wet towel into a cup. Nobody had taught you how to organize things. Many children your age had trouble tying their shoes. You were amazing."

"But I wasn't distinguished in kindergarten," I said.

"No," she said. "You looked so chubby and healthy that they put you at the front row to show off to visitors. You must've hated it. You didn't talk to people."

"A kindergarten teacher knew your parents, and she was very interested in you. One day I went to pick you up, she told me you wouldn't talk to her. I asked why you didn't talk to your teacher. You said, 'Auntie, she asked me all those questions about my family!' I couldn't believe it; you were only three years old."

"You always got sick at kindergarten, but were very well when you stayed at home. We took turns to baby-sit you, and you were easy to look after. Your uncle once left you home alone to take a nap, and put a few biscuits by your pillow. You woke up, ate the biscuits, and crawled about the bed. You knew no one was home, so you didn't cry."

"I wasn't naughty," I said.

"You were never fussy, and always sweet. You were never a kid."

She went on. "You saw everything about the adults, and loved your grandma and me the most. Grandma used to get off work, exhausted. She came home, lying on bed, and you would crawl onto her stomach. You two would play and giggle for about an hour, until she was relaxed and refreshed, then got up to cook dinner."

"Grandma did heavy labor at the factory. Seeing you sick all the time, she wanted to quit her job and keep you at home. She never gave up the job but wore herself out, for the sake of her wages that our family needed. That was the sort of life we led, with little money and lots of affections. You were a sweet, sensitive kid."

"Everybody loved you," she said.

I nodded, and ventured to tell her my story:

"When I turned seven, it was hard for me to return to my parents, who were strangers to me. I didn't know why I had been sent away, why I came back, and why it was my home. I was confused and depressed. For three months, I wouldn't call Mom and Dad: these names made no sense to me."

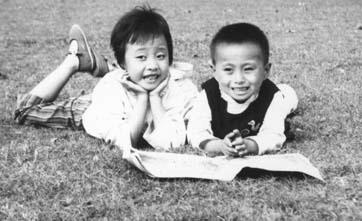

"I loved my brother right way, and we became inseparable playmates. I ran along with him, climbing trees, jumping off walls and rolling down slopes. He was fearless, and I was no less brave than he. I never owned a doll or any other toys; I had a naughty brother who was the best sport in the world."

"Then you began to change," my aunt said.

"I suppose I did." But I had had no idea what I would become.

Mom had told me, "You've wasted all these years at your grandparents' house, uneducated and eavesdropping."

In the summer before I started school, my mother taught me to read. After two months of home tutoring, I had learned enough to skip the first grade.

"You're fortunate to have come home," Mom said. "Now you may have some kind of a future. If you had returned years earlier, you might've turned out to be a prodigy."

Why had I been away for so long? Whose fault was it? My new life agenda blotted out my past, to which I was bonded for life. I missed the love that I had; once again, I was not able to keep it, this time, for my own good. What choice did I have but to be thrown into life's confusions? Unfortunately, I was never callous enough not to be confused.

After a long silence, my aunt said, "Your mother was partial to your brother."

"Was she?"

"It was so obvious. She always fed him good food, and said he was small. To make it fair, your dad tried to favor you."

"I sensed there was something different about Mom and Dad, but I never figured out what it was."

"It's a terrible thing to say, but you know we all loved you. We didn't like to see how far she carried her partiality to your brother."

As early as I could remember, Mom had spoken dreamily to my brother about his future manhood. She said little about me, except that a girl should be good, very good.

"I had a difficult adolescence."

"But you seemed to have nothing to fret about," my aunt said. "On top of your obvious qualities, you were so together."

"Are you kidding? I was anything but together."

I was thoroughly confused about love. I craved for affection and intimacy to thaw my unease at home, but I didn't know where to look. I had seen too much of my brother to fall easily for another boy. I had friends, boys and girls, and I honestly believed I was the same casual friend to either sex. I did not yet see the delicate correlation between female beauty, her self-esteem and sense of entitlement for privileges and prestige.

It wasn't self-esteem but self love that I lacked, and sensual love could not make me whole. I began my struggle for lofty self-acceptance, and took upon myself the gigantic burden of being the daughter, the oldest daughter who could fulfill every wish of her parents. I excelled in every area where my brother failed. It was a miracle that we grew up with only love for each other. I could hardly imagine the pain I had caused him during those years.

"Nobody knew my pain," I told my aunt. "I never felt at home with my parents."

"You were a dangerous girl," she said. "You were so difficult, yet seemed so easy, so sensitive, but not the least fussy."

No wonder I rarely got what I needed, but I could be as headstrong as my mother was partial. After many years of my brother's academic letdowns, Mom actually turned around to pamper me. I remembered hating her hypocrisy; I thought conditional love was wanton love. I thought I could tell love from hypocrisy, but I was wrong.

When my brother had a stomach ulcer, Mom told me she wouldn't want to live if he should not make it. Her gravity hurt me and scared me so, as I alone did not make her the mother she was; she loved us, losing one of us she would be too incomplete to exist. Bearing such passion she was bound to err. If love turned into poison, love was not at fault, judgment was, but what power did judgment have over boundless love?

"So I learned the price of intimacy," I said.

"Your mother made you."

Indeed, I became wary of intimacies: they might be terribly short-lived, or with a terrible price. I was not born with the right to demand love, even from my mother. Love is too precious; it is the medicine, not the food of life. We ask for love as if it could fall from the sky like rain. Maybe it would, but it falls with a price that can be dear.

My life does not have to lack because my mother had not given me the perfect love. Even though she once gave me up to earn the material things that our family needed. She thought me less than my brother because I was a girl. She belittled my love, therefore suffered my sneer when she decided to love me again. There was no making up for any loss in life, big or small. My mother did not give me the love I needed, but she gave me her best. I would not blame her.

I would not blame my folks, least of all my mother, for the life stories that helped mold my personality. The women in my family, my aunt, my mother and grandmother, each recollected my childhood from a personal standpoint to show what was at stake to care for me at that difficult time, how she made sacrifices to nurture my growth, and how she could have done better in hindsight. The truth is that they all have done their best, and they could never have done better. Perhaps it is only because they have told the stories that we begin to see the possibilities. Still, my life was as good as it could be under the circumstances. I cannot change what had passed; instead, I am given the means to re-story my life.

This is one of the many reasons that I write.